History: The Paiutes

|

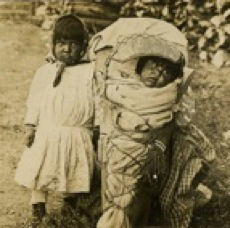

Scholars suggest that the Southern Paiutes and other Numic speaking peoples began moving into the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau around 1000 A.D. Prior to contact with Europeans, the Paiutes’ homeland spanned more than thirty million acres of present-day southern California, southern Nevada, south-central Utah, and northern Arizona. Their lifestyle included moving frequently, primarily according to the seasons and plant harvests and animal migration patterns, and they lived in independent groups of three to five households. Major decisions were made in council meetings. The traditional Paiute leader, called niave, offered advice and suggestions at council meetings and would later work to carry out the council’s decisions. The Spanish settlement of the American Southwest brought disruption and violence to the Southern Paiutes. Most importantly, the Spanish introduced the violent slave trade to Great Basin Indians. Because the Paiutes did not adopt the horse as a means of transportation, their communities were frequently raided for slaves by neighboring equestrian tribes, New Mexicans, and, eventually, Americans. Slave trafficking of Paiutes increased after the opening of the Old Spanish Trail, a trade route that connected New Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. The demand was highest for children, especially girls. Though the mid-1800s the Southern Paiutes had encountered Euro-American traders, travelers, and trappers, but they had not had to deal with white settlement on their lands. In 1851, however, members of the LDS Church began colonization efforts in the area of southern Utah, and by the end of 1858, Mormons had established eleven settlements in Southern Paiute territory. Initially, the Paiutes welcomed the Mormon presence, as it offered them some protection against raiding Utes, Navajos, and Mexicans. Unfortunately, Mormon settlement also brought sweeping epidemics. In the decade following settlement, some Paiute groups lost more than ninety percent of their population to disease. Eventually, the large number of Mormon settlers also led to competition over Paiute lands and resources. One of the most controversial events involving the Southern Paiutes occurred in September 1857 near what is now Cedar City, Utah. At the Mountain Meadows Massacre, more than one hundred emigrants bound for California were attacked and murdered. For over a century, the common history was that Paiute Indians first attacked the wagon train. The Paiutes then supposedly appealed to LDS settlers for aid, and the settlers approached the emigrants under a flag of truce. After convincing the emigrants to give up their weapons, the settlers led the wagon train to a secluded spot where they subsequently slaughtered most of the emigrants. Here again the Mormons claimed that Paiute Indians took part in the treachery, and for years the Paiutes bore the brunt of the blame for this tragic event. While many aspects of the massacre are still shrouded in mystery, it is important to stress that Paiute oral tradition strongly indicates that the Paiutes did not participate in either the initial attack or the following massacre. The first Paiute reservation was established in 1891 on the Santa Clara River west of St. George. The reservation was formally recognized by the government in 1903. In 1916 President Woodrow Wilson issued an order which expanded the size of the reservation to its current 26,880 acres. Three other Paiute reservations soon followed. The reservations proved too small and resource-poor for the Paiutes to sustain themselves, and the Paiutes were often dependent on Mormon charity and the federal government’s good will. That good will ended abruptly in the 1950s under the federal government’s policy of termination, which was intended to enforce assimilation and encourage self-sufficiency among Indian tribes but instead had devastating social and economic consequences. Prior to 1954, each Paiute band, except the Cedar Band, had its own reservation and functioning tribal government. However, under termination these bands lost federal recognition and, therefore, their eligibility for federal support. Many reports indicating that the Paiute tribe was not prepared for termination, and it is still a mystery as to why they were selected to be part of the program. The Paiutes suffered immensely under termination. Nearly one-half of all tribal members died during the period between 1954 and 1980, largely due to a lack of basic health resources. Without adequate income to meet their needs, the Paiutes could not pay property taxes and lost approximately 15,000 acres of former reservation lands. A less tangible, but equally important, result was the Paiutes’ diminishing pride and cultural heritage. In the early 1970s the Paiutes began concerted efforts to regain federal recognition. Finally, in 1980 Congress restored the federal trust relationship to the five bands, which were reorganized as the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah. Under restoration, the Paiutes received 4,770 acres of generally marginal reservation land scattered through southwestern Utah, only a fraction of the land they had lost under termination. Today the Paiute tribal government has improved healthcare and education on the reservations, and the Paiute Economic Development is working to create job opportunities close to home. With a landbase now in place, the Paiutes are finally becoming a visible presence in southern Utah. Their annual Restoration Gathering brings attention to the pride and heritage of the Paiute people. |

The Paiutes trace their origin to the story of Tabuts, the wise wolf who decided to carve many different people out of sticks. His plan was to scatter them evenly around the earth so that everyone would have a good place to live, but Tabuts had a mischievous younger brother, Shinangwav the coyote. Shinangway cut open the sack and people fell out in bunches all over the world. The people were angry at this treatment, and that is why other people always fight. The people left in the sack were the Southern Paiutes. Tabuts blessed them and put them in the very best place.

The Paiutes trace their origin to the story of Tabuts, the wise wolf who decided to carve many different people out of sticks. His plan was to scatter them evenly around the earth so that everyone would have a good place to live, but Tabuts had a mischievous younger brother, Shinangwav the coyote. Shinangway cut open the sack and people fell out in bunches all over the world. The people were angry at this treatment, and that is why other people always fight. The people left in the sack were the Southern Paiutes. Tabuts blessed them and put them in the very best place.